THE ROAD TO PATHFINDER

Husfjellet mountain

March 27th, 2019 - 12:57am

“We have to leave!” yelled Louise. We could barely understand her through the intense wind and snow blasting the walls of the tent, sounding more like waves crashing on the side of a boat. It was very clear, we did in fact need to leave. An unexpected blizzard had crept up on us. Heavy snow started to crash down on our tents situated just a few hundred feet from the peak of Husfjellet mountain. The team had no choice but to escape into the pitch blackness of night down to the base camp we had built earlier in the event we would need to evacuate the mountain quickly. This was no easy feat, we needed to carefully choose our steps yet walk as swiftly as possible down a mountain, in the darkness, during a blizzard, on a narrow and unmarked path, surrounded by jagged cliffs that dropped hundreds of feet. We gathered all the expensive film equipment and left the rest behind hoping we could locate the tents the next chance the weather would allow us to ascend the mountain. We were already half-way through our 24-day production in Norway, and we were running out of time. The Northern lights, the phenomenon that brought us to this remote part of Norway in the first place, was still nowhere to be seen.

The PATHFINDER team climbs Husfjellet mountain

The journey to create PATHFINDER began at the closing of 2018. A passion project created by Raised by Wolves, a collective of like-minded filmmakers that are dedicated to creating films that tell stories of human passion, nature, and adventure, while attempting to provoke thought & environmental responsibility.

We were approached by Israeli photographer, friend, and slack-liner Kfir Amir who told us that a group of his friends, all professional slack-liners from all around the world, planned to head out to Norway and attempt to walk a slack-line beneath the Northern lights. We are always up for a good challenge and we fell in love with the idea. After deciding to move forward with the project, it was time to figure out the story.

Determining how to tell a story is always a challenge. A good story doesn't necessarily need to be shocking, or outrageous. For us, a good story is something that stays with the viewer, sparks dialogue, inspires, and hopefully, in the case of our collective, leads to positive change & growth. At the time we couldn’t figure out what the story was. We didn’t want to follow the “will they make it?” formula for the documentary. We wanted to transport the viewer to the wilderness of Norway. We wanted them to experience the raw nature, the bitter cold, and the unique culture. We wanted to leave our viewers inspired, and for some, perhaps even provide a platform to re-examine their lives. After all, this film glorifies people who live their truth unconditionally.

We turned to Google and YouTube, learning everything we could about Norway, local folklore, the indigenous Sami culture, the sport of slack-lining, and what it means to be a slack-liner. We decided that the descriptions we aimed to achieve in the culmination of this film would be adventurous, inspiring, emotional, with a rich story and incredible cinematic visuals.

PATHFINDER Mood Board

Three months after our meeting with Kfir, we had a script in hand that excited us. We named it PATHFINDER after an old tale in Sami folklore. Our script focused on three main aspects: the Norwegian nature, the indigenous Sami folklore surrounding the Northern lights, and the slackliners’ inspiring message and insight on life. Once we had the script it was time to research everything we needed to know prior to kicking off the logistics of production.

We divided our research efforts into a few categories: equipment, location, aurora borealis

EQUIPMENT

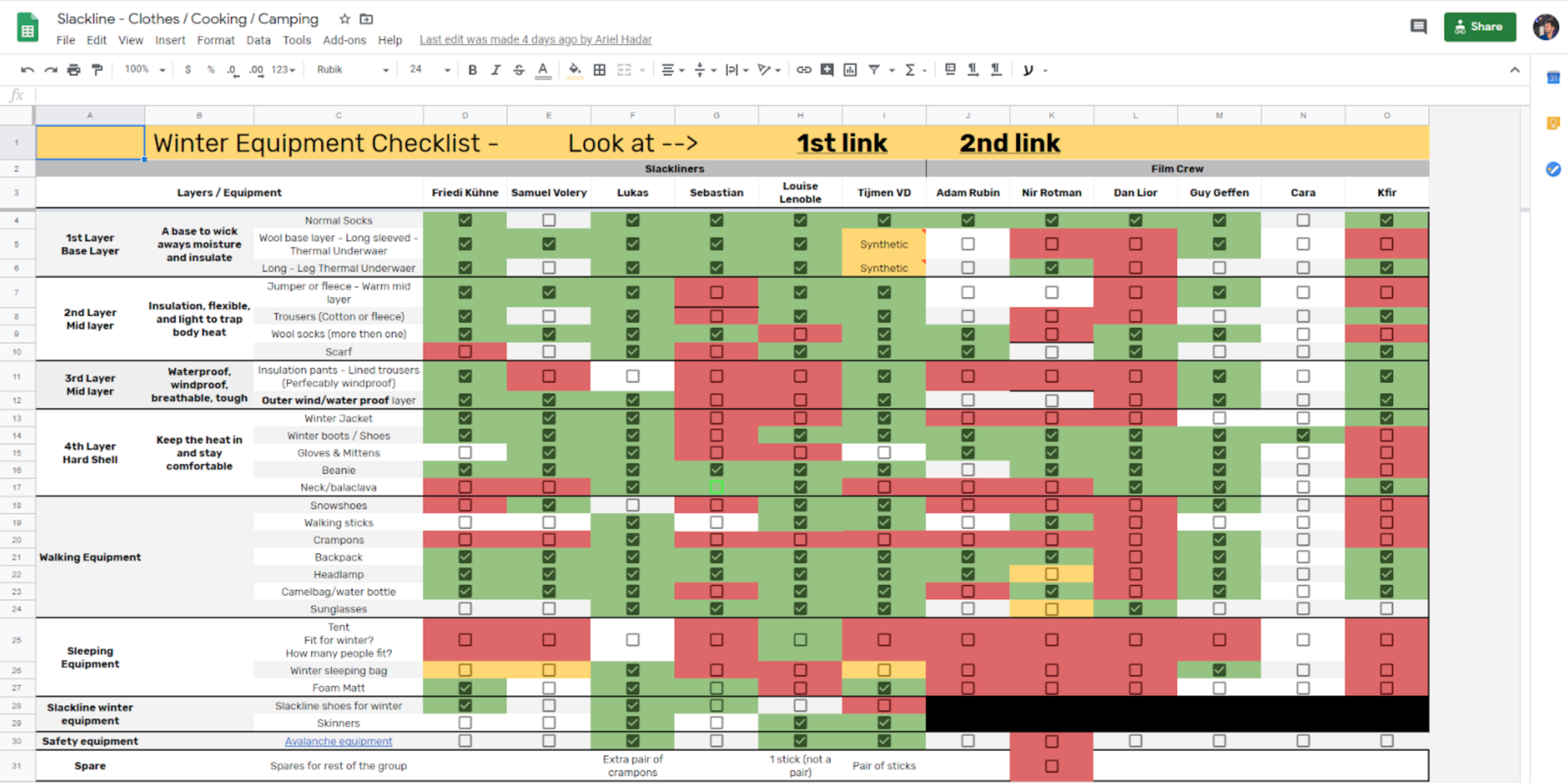

Our research taught us that the conditions we were about to face would be, even conservatively speaking, extremely harsh. It was crucial for us to select the right gear for the production that could withstand the elements and for us to master how to properly care for it under the arctic conditions. We gathered all the information we could find on the internet. It came down to a few simple guidelines. Carry each piece of equipment inside a ziplock bag, accompanied by silica gel packets in each bag to absorb the humidity and prevent the lens from fogging up. From previous experience, we knew how fast batteries deplete in cold weather so we knew we would need to pad the batteries in the bag compartments with heating packs.

More critically, we needed to know what kind of clothing and footwear were necessary to stay safe. We consulted with our friend Nadav Ben Yehuda, a world-renowned alpinist who instructed us about what clothing we would need to stay warm. The method we were instructed to follow is known as the onion layer method. Meaning, each person would need to have multiple layers which they take off according to how hot they are, just like an onion. The layer system included underpants & undershirt, topped with a fleece jacket, on top of that a down jacket, and on top of that a windbreaker which would stay on no matter how many layers we would take off during our filming days.

The Through equipment checklist made by Adam Rubin

Considering how many tasks would require us to take our gloves on and off, we were instructed to place heating packs in the pockets of each layer, to always have a place of refuge for our fingers no matter which layer we were up or down to.

For the film crew, we chose gloves by the Heat Company that allowed us to not only interchange between mittens and individual fingers (supporting touch screen), but they also have a special compartment for heating packs.

LOCATION

Productions such as this demand you to learn everything there is to know about the location prior to arrival to make sure you are prepared for anything that might arise. We researched Google Earth, created maps highlighting gas stations, equipment stores, stores to stock up on food, emergency clinics, even alternate routes in the event of an avalanche which is common during that time of year (March-April). We marked the main roads and driving distances and pinpointed specific locations we found on Instagram & Google that seemed like they would fit the powerful nature we wanted to portray in the film.

The ground plan for Senja

AURORA

The aurora is one of the most elusive sights on the planet. So many things must align together in order to see a beautiful and bright aurora. At the end of the day, it’s not something you can control, yet we had to learn how to predict it in order to make sure we had the best chances of capturing it, something which was crucial for this project’s success. We consulted with Guy Geffen, a photographer and aurora tour guide living in Lapland. Guy explained what to notice when hunting down the aurora and which apps and websites to use for guidance. “My Aurora” and spaceweathernews.com became a daily tool used every morning and night throughout the production.

Once production started, Guy joined on board as part of the team and drove to Norway to help us out as a time-lapse photographer and the team's weather & aurora forecaster. Each day, Guy would measure the solar wind data and observe the sun’s surface. This greatly improved our chances in capturing the elusive shot we were after.

FINDING THE SPONSORES

Pre-production started in mid-January 2019. We had all the information necessary to start our journey but the next step was figuring out how to make it all happen. There was no client paying to make this happen, so funding the entire project was our next roadblock. We started by creating a treatment to explain the vision of the film, this included the script, scenes breakdown, the music we wanted to use, the visuals we wanted to get, and a brief rundown of the team that was taking part in the production. We added previous works and references to strengthen our message and show that we are capable of achieving the challenge at hand. Once the treatment was ready, we created a “Call for Sponsors” document which provided all the information necessary for brands who were interested in taking part. The “Call for Sponsors” broke down the timeline, what we needed from the brands, and what content we would provide in exchange. Our next step was probably the least fun, getting in touch with as many different brands as possible with the goal of a few of them joining on. We sent out emails, LinkedIn and Facebook messages, phone calls, contact forms, really any method we could think of to reach out to the brands we wanted to work with. In the end, after many emails, messages, and phone calls, our first sponsor signed on. Northface agreed to fit all of the production team and slack-liners with a winter wardrobe including sleeping bags and backpacks. While Baffin shoes, a footwear company located in Canada, supplied each member of the team with shoes that protected our feet up to -70C. Sony provided us with some of the best lenses and a camera to capture the aurora. Additionally, Drytech supplied us with freeze-dried meals to eat on the mountain, and Hamn I Senja is an awesome local hotel that provided us with a home base and lodging throughout the filming and production.

Simultaneously, we started looking for the right fixer to make this project happen. To those of you who are unfamiliar with what a fixer is, it’s essentially a necessary role in any production that requires remote controlled production and working with local communities. A fixer has to be a resourceful person with a deep knowledge of the surroundings and community, preferably one who speaks the local language. A good fixer is communicative, innovative, and all-around a great problem solver. We checked online and eventually one of our sponsors, Hamn I Senja led us to Espen Minde, a local tour guide living in Senja who agreed to help us with scouting for the right location. During our conversation with Espen we also found out he was of Sami descent and his mother knew a Sami Shaman named Pierra who lived about an 8 hour drive from where the team would be staying. We asked Espen if he could get in touch with the Shaman, and a few days after we were given a few dates to select from where we could film Pierra performing a Sami ceremony where he would bless the team on their quest to find the Aurora Borealis.

Our Shaman, Pierre during a short break between shots.

We made a lot of progress in a short amount of time throughout pre-production, but we still had our final and biggest roadblock ahead of us. We were 2 weeks out from the dates we planned to fly to Norway and begin filming, we had everything we needed, except for a way to actually finance the entire project. We needed to be able to pay for everyone's flights, transportation, ferry to Senja, and not to mention the outrageous overweight fees we knew we would be paying to haul all of our heavy gear. We were literally on the verge of giving up when Adam Rubin, the Co-Creator of the project, approached one of his clients Lycored and they agreed to fund us. Suddenly PATHFINDER was actually happening and soon after, the entire team had their tickets booked.

Pre production travel sheets

Production started on the 14th of March. A small recon team made up of Espen the fixer, PATHFINDER Co-Creator Dan Lior, and Tijmenn, a representative from the slack-line team landed in Norway early in order to scout for the perfect location to shoot the film. We had a few crucial parameters while looking for the perfect spot and they all had to be fulfilled in order to create the film we wanted. First, the slack-line location had to be visually inspiring. Nature would play such an important role in the film and we wanted our viewers to be in awe of the visuals. We aimed for peaks overlooking the fjords or distant mountains. At the same time, the conditions had to be optimal for the slack-liners to be able to put up a Highline and walk it safely. The last key was the Northern lights.

The simple drawing we have sent to our fixer to showcase how the Aurora shot needed to look.

Not only did we need a captivating peak to put the highline up, we also needed the camera to face in the right direction to be able to see the lights behind the slackliners as they were walking the line. The first 3 days were dedicated to finding the perfect spot, luckily for everyone involved (especially for the recon team) we managed to find our location after climbing the second mountain, making Husfijlet peak our setting. Even though we found our location, we did notice just how fickle the weather was and how risky the approach to the line can be. Considering the Northern lights are extremely unpredictable, we decided to create another highline as a backup closer to the hotel in the case Husfijlet was ever inaccessible.

Once we found our mountain, and the rest of the team landed in Norway, it was time to get our hands dirty, or should we say snowy. Upon everyone's arrival, we sat down for an opening conversation, pitching the look & feel of the film and sharing our vision of how it would look.

The following day we ascended Hufijlet mountain with Espen, our local guide. The goal was to prepare the ground for filming and make sure it was as safe as possible for the film team who did not possess the same alpine experience as the slackliners. That meant setting up our base camp an hour climb from the summit and making sure the approach to the summit was as safe. Espen, along with the slack-line team cleared off obstacles, took down ice shelves, and created snow anchors with ropes connected to each one on to which the film team and slack-liners were able to safely secure their harnesses while walking the slippery ridge of the mountain.

The peak of Husfijlet mountain during the rigging of the slack-line.

The following day, the team set up a tent on the summit to allow a fast approach in the case the Northern lights were to reveal itself. Finally, after many months of preparations, we pressed the record button on our cameras for the first time as the slackline team finally started rigging up the Highline in a high dense fog.

The peak of Husfijlet mountain, taken during our first ascension

Throughout the following few weeks, the PATHFINDER project truly lived up to its name. Almost every single day we climbed 5-6 hours up the mountain only to see an ominous whiteout storm approaching from the north which would send us sometimes literally running back down. A few times the storm would take us by surprise and we would find ourselves not knowing which way is right or left. We lost count of how many times we walked up the mountain. Some days we were extremely lucky and the skies were clear enough for us to spend a few good hours shooting the team walking the line, and sometimes we would climb all the way up, reach the peak, and understand that in an hour or less, remaining on the peak might become dangerous.

A notable mention is that our project took place exactly during “avalanche season” so each step and the angle we would walk down the mountain also posed great significance. Eventually, the amount of time we planned to stay in Norway worked out to be exactly what we needed and we were able to have a few beautiful days where we filmed the entire team walking on the line. From a personal perspective, it was a beautiful thing to witness the team walking the line, something that brings them so much joy. It was truly a sight to see. At times, we all lowered our cameras and just enjoyed being present in the moment.

Slackliner Lukas Irmler on the line

From our early research on the weather, we knew that some days would just not allow for shooting outdoors. Considering we always wanted to incorporate interviews of the slack-liners in the film, we decided to have an interview studio set up to be used during the especially stormy days.

THE EQUIPMENT WE USE

From very early, we knew we needed to be very smart regarding the camera gear we would use for the film. Our main camera was the Sony FS5. We chose it for its mobility which serves as a great camera for documentary work. We fitted the camera with an Atomos Shogun to get the best image quality possible. For the Aurora lights, the obvious choice was the Sony A7S II known for its incredible low-light capabilities. For B-roll & stills, we had a Canon 1DX Mark II and a Sony A6300. As for lenses, we used lenses lent to us by Sony and our own personal Canon lenses with fitted Metabones.

The drones we used for aerial shots were Mavic 2 Pro & Phantom 4 pro. Initially, we were worried about how well they would perform under the weather conditions as lithium batteries tend to run out extremely quickly in cold temperatures.

Cold temperatures were something we had to handle daily and made filming extremely difficult.

Interviews were an extremely important aspect of the film. We wanted to make the film feel personal to the viewer. Each of the slackliners had a really interesting message and insight on life, a message that has been told through the entirety of humanity, follow what inspires you, leave your comfort zone behind, and go out there and do what makes you happy. We wanted that message to feel personal to the viewer. We figured the best way to achieve this was to have direct eye contact with the subjects who were speaking. Real eye contact makes everything much more sincere, and as every filmmaker knows, talking to a camera lens can be awkward or uncomfortable for an interviewee. We found our solution with EyeDirect, a device that allows the interviewee to look at the interviewer’s face rather than a lens, making it feel much more like a natural and normal conversation.

To make sure everything was organized and well prepared for the intense days of shooting we came up with a smart system to help us keep things in order. We dedicated one room given to us by Hamn I Senja for the production team’s equipment.

We had over 8 cameras and we needed to make sure that all the batteries were charged and all memory cards were correctly off-loaded so everything was ready for each day of filming. This wasn’t easy so we came up with a smart “conveyor belt” system where each night we would return and put all of the used batteries in a plastic container, and all of the used cards in another. We used stickers that were placed on the cameras to mark each card so we knew what camera we used and with the use of a spreadsheet we made sure nothing was forgotten.

Each night we would return to the hotel, drop our cards and batteries, and then the production assistant would charge all the batteries through the night and offload the entire materials all while preparing and cleaning the gear for the next day.

THE SLACK-LINERS

Creating a documentary is no easy task. The pressure of filming, getting the equipment ready for each day, offloading material each night, scheduling, planning, making sure nothing is forgotten is really only half of the project. The other half relies solely on the subject you are documenting. Your connection with your subjects is also crucial. Luckily for us, the slack-liners were more enthusiastic and determined to accomplish the perfect film than we were. Without a doubt, the slack-liners helped push us forward each day, mentally and literally up the mountain. We are talking top-level athletes who on more than one occasion ended up carrying not only their own equipment but also ours in an effort to reach the summit for only an hour to allow us to film before an incoming storm would beat us to it. The peak was risky, slippery, and at times unstable due to shifting snow. When the slack-liners were not walking the line, they accompanied each one of the production team, making sure our safety harnesses were hooked to the snow anchors and helped us out with whatever was needed. We couldn’t really ask for a better team.

GETTING THE SHOT

Getting the actual shot was the biggest challenge. We purposely chose to spend a long time in Norway since we knew just how rare it is to see the aurora, especially a good, bright, and strong one. The original plan was to capture the aurora on the peak of Husfijlet mountain. That was the reason why we built the camps and stored them with food, gas to cook, sleeping bags, and extra heating packs. The plan proved to be more difficult than we initially thought and one night, a small team slept on the mountain and were woken up by a blazing storm leading us to a very tense and difficult walk down the mountain in the darkness. Luckily we had a plan B and upon arriving in Norway. We rigged another line on a more approachable mountain that we could summit quicker.

We spent almost a weeks’ worth of nights on the backup line with the film team standing, cameras ready, and the slack-liners taking turns sitting down on the line waiting for an opening in the clouds. Some nights were clear with no aurora, some nights had the faintest green light in the sky. One night, while we were all eating dinner the sky blew up. Guy, our northern lights expert happened to be on a supply run and called us screaming that we must get to the backup line as fast as possible. By the time we did, the aurora was long gone.

This made us realize that no matter the weather forecast if there was the slightest chance an aurora was to shine, we had to be waiting and prepared for it. Even with an up to date forecast, the weather was extremely unpredictable due to being so far north. Nights that were supposed to be cloudy were sometimes completely clear, and nights that were supposed to be clear and full of Aurora proved to be more cloudy. Sometimes we could see the aurora blazing behind the clouds leaving us hoping, crossing our fingers for the slightest opening.

Out of 24 days, we managed to have only three nights, one of which was filled with clouds. It was only on the last night of principal filming that we actually managed to get the aurora we were searching for.

SCREENING / EDITING PROCESS

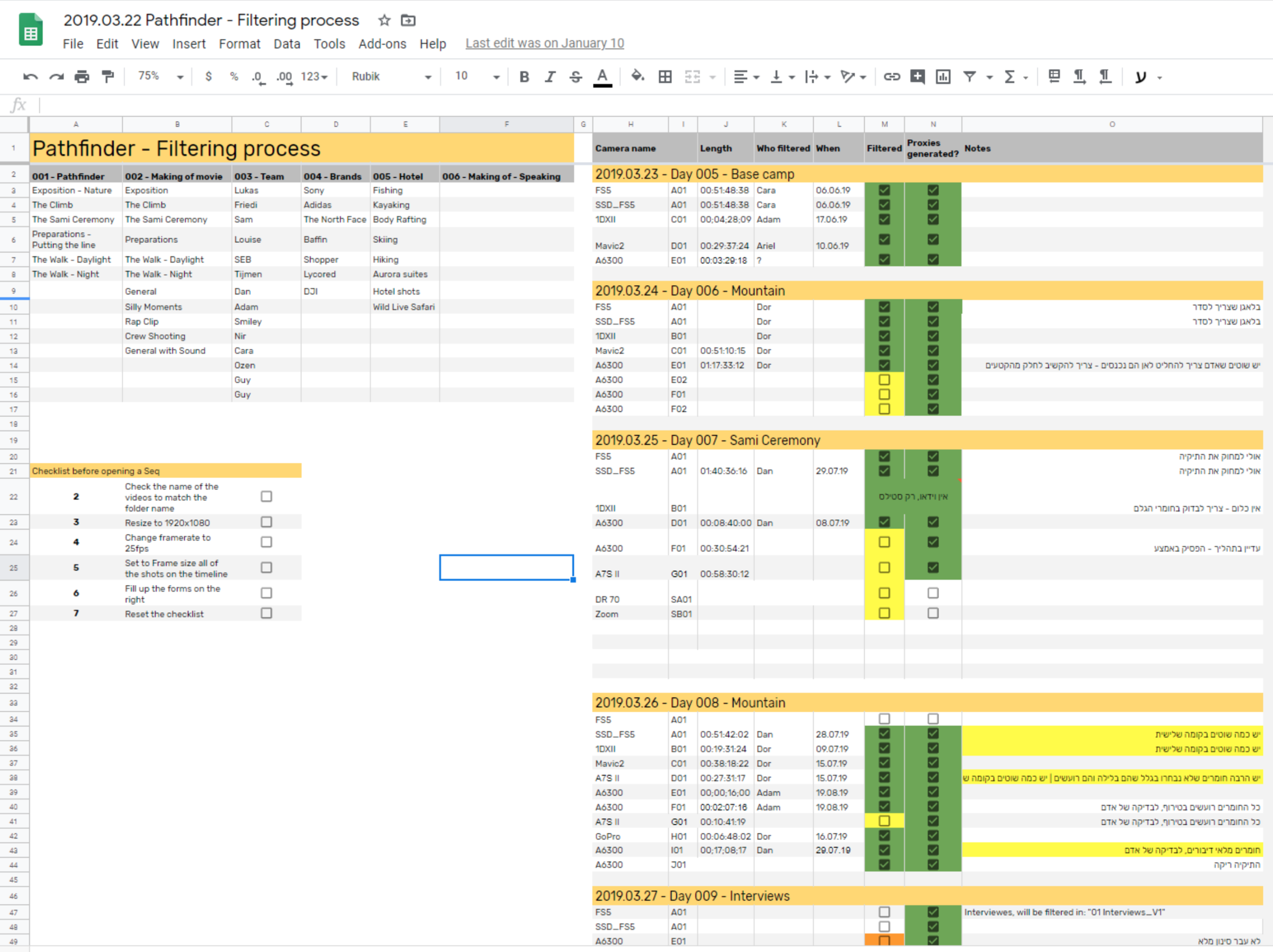

We returned with over 18TB of footage from Norway. Over 8 cameras were used in the process of filming and we needed to come up with a system to allow us to be as efficient as possible throughout the editing process.

We decided to use Adobe eco-system as we were most familiar with it. Our greatest challenge was just how much footage we had and how varied it was. We needed fast and easy access to be able to edit not only PATHFINDER, but also all the content we owed to each of our sponsors in our agreement. We ended up dividing the film into different categories as follows:

Exposition

the Climb to the Mountain

Preparations of the gear

Rigging the line

Walking the line at day

Walking the line at night (aurora),

Sami ceremony

Under each category, we created additional layers signifying which of the eight cameras was used for the shot. We applied the same method to our sponsors, creating “marks” for north face, Lycored, Sony, Baffin, and Hamn I Senja. Considering we wanted to create another short promo video for each of the slackliners and team members as a thank you, we created another sequence containing the whole team. We then moved on to screen all the footage and applied it to the appointed marks at the same time.

So, for example, if we were looking at footage from the FS5 of Tijmen walking up a mountain, we would immediately allocate that clip to:

PATHFINDER || THE CLIMB || FS5

BRANDS || BAFFIN || FS5 || NORTHFACE || FS5

TEAM || TIJMENT || FS5

This system allowed us to immediately find any kind of footage we needed in a fast and efficient way.

Finally, we needed to go over 16 hours of interview footage with the slackliners. For this, we created a similar system where we had a name layer signaling who the person talking is in a particular sequence. We then screened through all of the interviews while creating a text layer with the “question” and another text layer with a short gist of what the “answer” was.

In that case, if we wanted to hear everything Louise had said about inspiration, we just needed to go to her section in the timeline, find the text layer mentioning “what inspires you?” And then screen through the different explanations she gave until we found the one suitable for the final edit.

It was a lot of work, but it would have been much more if we hadn’t come up with that system.

It took us months to screen through the material and eventually edit the film. The ending result, as documentary films often go, ended up telling a very different story than what we had first anticipated.

CLOSING WORDS

PATHFINDER was without a doubt the most difficult and challenging project each one of the team members has ever faced. It required innovation, patience, and grit. We really feel that not only did we make a film that we are proud of, but also a film others to which others can connect. The message applies to everyone who wants more from life. Everything is possible, all you need to do is leave your comfort zone and grab it.

The PATHFINDER team

PATHFINDER WAS PRODUCED BY RAISED BY WOLVES

Raised by Wolves was founded by Dan Lior, Adam Rubin & Edden Ram in 2019. We are a film production company; a collective of like-minded filmmakers that are dedicated to creating documentary films that tell stories of human passion, nature, and adventure, with the hopes of provoking thought & environmental responsibility.

For more information on the film please visit www.pathfindermovie.com

We’d be happy to hear from you

Dan and Adam, the founders of Raised by Wolves & creators of PATHFINDER seeking refuge in a snow tunnel to plan an upcoming shoot during a very windy afternoon.